Ever since I started curating and editing the GYA blog, the rest of the GYA team has heard time and time again my obsession with the active voice. Action verbs produce strong writing. If my bio on the GYA website didn’t focus on my work in global education and Fair Trade Learning, it would express my strong desire to make the world a better-written place. What does this have to do with experiential education? Keep reading, you’ll see!

The terms experiential education, comfort zone stretching, and intercultural engagement each refer to ideas that hold the container around a gap year experience. Browse GYA’s Member Programs’ and Consultants’ websites and you will see the value that each of them place upon these important ideas. While tone-setting from the program or consultant is important, it’s up to the gap year student to bring these concepts down to earth as active drivers of their own learning. Program providers facilitate experiential education, comfort zone stretching, and intercultural engagement curricula; but the students learn experientially, stretch their own comfort zones, and expand their world views through actively engaging with cultures different from their own. The decision to take a gap year, or to enroll in a global education program is an important first step. However, programs do not do the learning for the student. The onus for learning and engaging is on the student, who must actively choose to show up for each present moment.

Here’s how I learned to show up for my own learning in practice, and my advice to gap year students ready to start their journeys.

Stretching My Comfort Zone for Language Immersion - Thailand 2018

I sat on the yellow linoleum floor in my host family’s kitchen in Thailand. My host mom spoke to her son, seemingly about how to cook the fish cubes in the ziplock bag that they both held. I thumbed through my Lonely Planet Thai Phrasebook looking for a way to ask them questions about how to cook or about their favorite meals, or anything else. I realized in that moment that my phrasebook was only useful to a point. If I wanted to practice speaking Thai, I had to practice speaking Thai. Language immersion is not meant to remain an abstract idea presented on a program website that passively sits on the ground while the student somehow absorbs words and grammar by osmosis. If I wanted language immersion, I had to meet the moment and immerse myself. Eventually, I brushed off the dust at the edge of my comfort zone and actually talked to my host family. I learned how to say delicious and likely pronounced the Thai word for fish wrong, and we all enjoyed laughing at my attempts to get new words out of my unaccustomed mouth.

This experience taught me about the active role I have to continuously choose to take in my own learning. It taught me that stretching my comfort zone is a moment-by-moment commitment to my own growth. The ideas of language immersion, comfort zone stretching, and experiential education inspired me to sign up for the program. However, the program couldn’t do the active learning for me.

Immersion doesn’t automatically happen because you enrolled in a program: It requires active participation.

Two Sides of the Same Boulder: Rogue River, Oregon - 2017

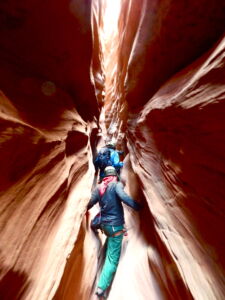

My feet ached in my drenched Carolina boots after 5 out of 7 miles down the Rogue River Trail in the pouring rain. My exhaustion weighed more than the 75-liter Osprey pack strapped to my back. We came up on an enormous black boulder with a very narrow trail carved into it. The boulder extended 20 feet above on my left and the cliff dropped off on my right. The rain gave the boulder a sleek and shiny appearance and I thought I’d slip and fall off. I was exhausted from my first backcountry trek, and I broke into tears when the program leader told us we still had two more miles left to hike after crossing the seemingly-uncrossable boulder. I didn’t think my body could take any more. I can’t remember if we sat or stood, but the program leaders supported me as I realized that there was no other choice but to continue moving forward. At the same time, I felt joy and gratitude looking at the vegetation and stream of running water embedded in the hillside behind us. The pouring rain soaked my clothing, my skin, and my bones.

My feet ached in my drenched Carolina boots after 5 out of 7 miles down the Rogue River Trail in the pouring rain. My exhaustion weighed more than the 75-liter Osprey pack strapped to my back. We came up on an enormous black boulder with a very narrow trail carved into it. The boulder extended 20 feet above on my left and the cliff dropped off on my right. The rain gave the boulder a sleek and shiny appearance and I thought I’d slip and fall off. I was exhausted from my first backcountry trek, and I broke into tears when the program leader told us we still had two more miles left to hike after crossing the seemingly-uncrossable boulder. I didn’t think my body could take any more. I can’t remember if we sat or stood, but the program leaders supported me as I realized that there was no other choice but to continue moving forward. At the same time, I felt joy and gratitude looking at the vegetation and stream of running water embedded in the hillside behind us. The pouring rain soaked my clothing, my skin, and my bones.

After about 20 minutes, I approached the cliff. The traction on my boots made it feel less slippery than it looked, and I kept my left hand on the rock face to help steady myself. I slowly made it to the other side. It’s safe to say that this was the most terrifying physical feat I had accomplished to-date. Two miles later, we reached our backcountry campsite, in less time than I thought. I was relieved. Everything was wet, and I was grateful to get my boots off and to finally attend to the blisters that had been burning inside those boots for six hours. Before that hike, I had no idea that I could, in fact, hike seven miles with a 75lb pack on my back. It was brutal and also wonderful.

After about 20 minutes, I approached the cliff. The traction on my boots made it feel less slippery than it looked, and I kept my left hand on the rock face to help steady myself. I slowly made it to the other side. It’s safe to say that this was the most terrifying physical feat I had accomplished to-date. Two miles later, we reached our backcountry campsite, in less time than I thought. I was relieved. Everything was wet, and I was grateful to get my boots off and to finally attend to the blisters that had been burning inside those boots for six hours. Before that hike, I had no idea that I could, in fact, hike seven miles with a 75lb pack on my back. It was brutal and also wonderful.

The morning of our hike back home, the sun greeted us and warmed our bodies as we filtered our water for the day and dismantled our tents. We leaped back down the trail with the sun shining down on us after a week of downpour. An hour in, we hiked across a large black rock. Halfway across it, I realized that this now-dry rock that I confidently crossed was the same slippery cliff from a few days before. The only differences were my perspective and the weather.

In the field of global and experiential education, we frequently discuss participant transformation using a caterpillar’s experience of transformation into a butterfly as a metaphor. Before a significant comfort-zone stretching and transformational experience, a program participant is like the caterpillar. The experience itself, an intense backpacking trip for me in this case, is like a cocoon with the person as the gooey material inside. Emerging out from the experience and reflecting on it to absorb the learnings from the experience is like the butterfly exercising its new wings, able to fly with confidence after emerging from the challenge. This was absolutely my experience through my first backpacking program. I learned that my body can withstand so much more than I ever thought it could (and I can enjoy this process). I had the opportunity to return to my college town with one of the trip leaders who only stayed with us for the front-country portion of the trip. But I didn’t take it. I trusted the voice that told me that I’d never know whether or not I could make the longer trek unless I showed up for the occasion. I’m so glad that I did.

Core Values and Cultural Practices: Northern Thailand - 2018

My cohort and I spent a day at Baan Kway Phan, a buffalo and fishing farm in Northern Thailand. We learned about modern-day subsistence fishing and how fishermen and their families weave elaborate bamboo baskets and nets to catch fish and eel from the river.

During our time in this community, we were invited to try our hand at fishing. I placed a snail in the valve-like bottom of a basket to trap an eel. However, when our trip leader Manop showed us how to hook a live fish at the end of a string and bamboo pole to catch larger fish, I couldn’t take my mind off of the image of the live fish struggling against the outside air and the hook piercing its body. It thrashed and writhed as oxygen filled its gills. When it was my turn to hook a fish, I made a strong effort to keep in mind everything I had learned about engaging with other cultures and actively pursuing the spaces outside of my comfort zone. However, I couldn’t bring myself to hook the fish. I teared up and couldn’t force myself to knowingly cause another living being so much pain. Manop met my tears with empathy.

In that same moment, another equally important reflection came up for me. At Baan Kway, fishermen use live bait as a neutral part of the fishing process to provide food for families and the community. The method carries no malice. The pain the fish experience on the hook is just a part of the process, and acknowledging this idea helped me fully understand the practice of subsistence fishing in Northern Thailand. In turn, I did not use this realization to internally diminish my own convictions.

For me, this moment didn’t feel like an opportunity to step out of my comfort zone. Instead, it felt like I would have to override my core values to participate in that activity. A step in that direction represented a step away from myself. In this reflective process, I learned that I could fully respect a practice from another culture while simultaneously respecting myself.

Pushing one’s comfort zone and pushing one’s core values are two different things. It’s very possible to actively engage with other cultures by interacting with community members and learning about what’s normal for them, while maintaining the joy of missing out (JOMO) when that feels necessary. If it’s a common practice to share a meal seated on the ground and I notice internal discomfort, I would take a moment to notice the feeling and then challenge myself to participate. This is the beginning of embracing the growth reaching for me from outside my comfort zone. This is stretching into new flexibility. In a different context, hooking that fish, knowingly causing pain to another living being, would have felt like overriding my core value to do no harm. Core values are different from learned conceptions of normal. This is not to say that fishermen in Thailand knowingly harm other creatures and feel fine with that. They don’t. From their perspective, using a live fish is a neutral part of the fishing process, and better for the environment than using plastic bait. Subsistence farming including live bait is a valid way to obtain food.

Further reflection: I’ve returned to this moment several times over the past year and I wonder if I would have had a different experience if I had spent a month instead of a day on that farm. I wonder if I would have found over time that my experience actually was about an internalized sense of normal that I had instead of a momentary discomfort. Either way, it was important to me to opt out of that particular activity at that particular moment, and listening to myself was the right thing for me at that time.

Through this experience, I learned that different cultural perspectives and values can co-exist. I can show up authentically and respectfully without overriding my values and without rejecting those of another culture. I’m using this particular example of engaging with another culture by observing to highlight that active engagement doesn’t always look like participating in every single activity.

Active learning is an ongoing commitment to learning actively

The path across that boulder didn’t grow thicker overnight while I was in my tent two miles farther down the path. The cliff path remained narrow. It was me who had expanded to the point where the path in front of me was no longer a big deal. I like to think that the rain from two days before when I experienced deep challenge in crossing that wet black stone, and then the sun that beckoned me to leap forward on the path back home was the Earth and the Sun’s external way of reflecting my internal growth back to me. I showed up in the storm. I embraced the sun-kissed growth sprouting from my heart.

Language learning and cultural immersion through a homestay don’t happen automatically because a program advertises these ideas on their websites. Learning a language and immersing oneself in it are choices to actively and consistently make.

Meet yourself where you are in the face of a challenge. Sometimes stretching your comfort zone will look like crossing a tricky boulder. Sometimes it will look like standing in your own core truth while wholeheartedly embracing the idea of another.

Be active. Turn each inspiring concept (e.g. experiential education, comfort zone stretching, language immersion, etc.) listed on your Program’s or Consultant’s websites into active verbs and make a plan for how you will actively show up to learn from your experiences, stretch your comfort zone, immerse yourself in a new language spoken around you, and so on. Providers and Consultants hold the program container, but you must take initiative for your own learning.

As a gap year student, your I can’ts will transform into I dids. You just have to show up and meet the challenge.

Elizabeth Bezark is a gap year educator who strongly believes in the power of global and intercultural engagement to craft deeper levels of shared understanding in our world. Infinitely curious, she loves using meaningful travel, adventure, and cultural immersion as methods for internal and external exploration and growth. Elizabeth uses these concepts both as internal compasses for her personal path and external compasses while fostering positive learning environments for others.

Elizabeth Bezark is a gap year educator who strongly believes in the power of global and intercultural engagement to craft deeper levels of shared understanding in our world. Infinitely curious, she loves using meaningful travel, adventure, and cultural immersion as methods for internal and external exploration and growth. Elizabeth uses these concepts both as internal compasses for her personal path and external compasses while fostering positive learning environments for others.

She is the Gap Year Association’s Associate Director of Communications, and supports the GYA-Accredited Irish Gap Year with their programs at full-time capacity in Donegal, Ireland.

Categories

- Advising (7)

- Alumni (2)

- Career (4)

- College & University (15)

- Communication (17)

- DEIA (4)

- Fair Trade Learning (3)

- Finances (12)

- Gap Year Benefits (67)

- Growth & Development (6)

- Leadership (5)

- Learning & Reflection (54)

- Mental Health (4)

- Planning (59)

- Professional Development (4)

- Research (4)

- Risk Management (3)

- Safety (5)

- Service-Learning (10)

- Standards & Accreditation (1)

- Sustainability (6)

- Voices Project (20)